Understanding how the brain develops automatic behaviours through neural pathway strengthening and repetition.

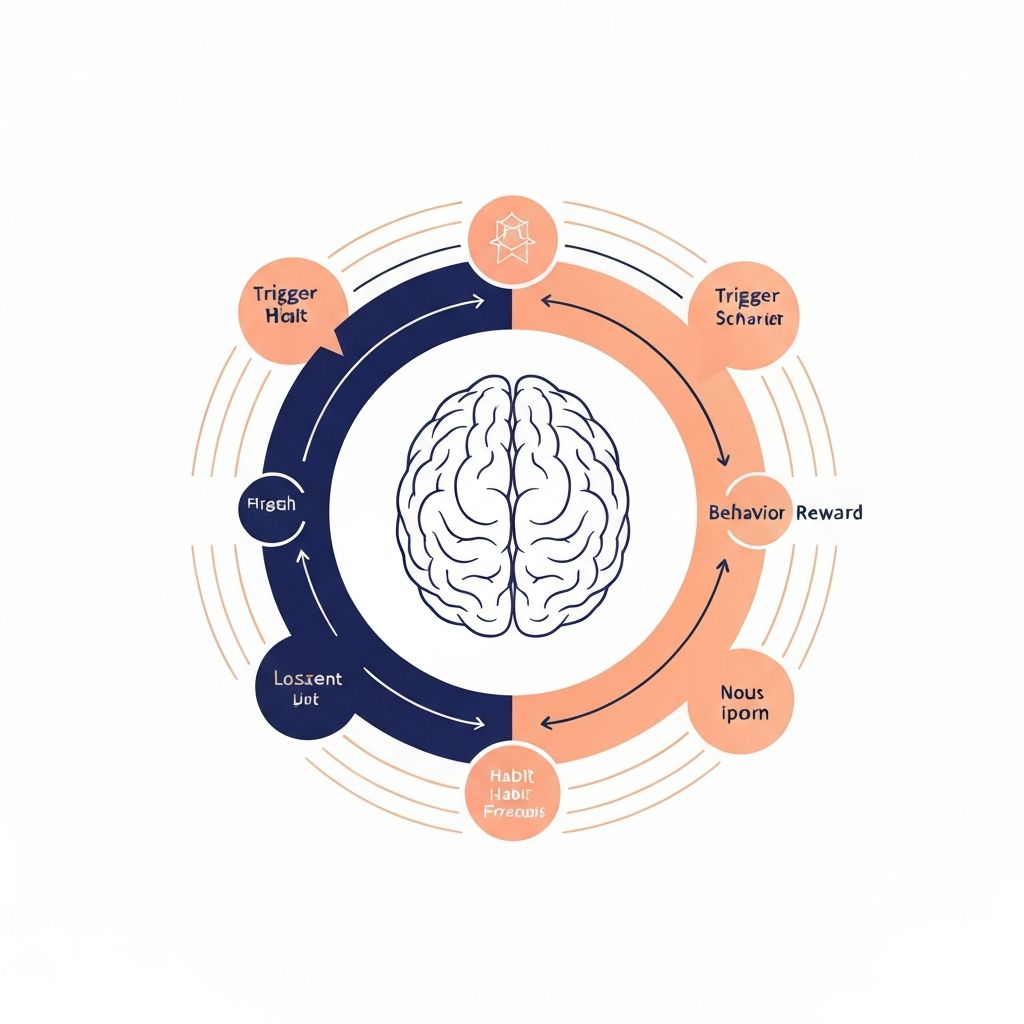

The brain is fundamentally a pattern-recognition and pattern-formation organ. When we repeat an action—particularly in consistent contexts with predictable rewards—neural pathways strengthen. This strengthening is the biological basis of habit formation. Each repetition reinforces the connections between neurons involved in executing the behaviour, making future executions require progressively less conscious effort.

In the context of eating, this process is particularly relevant. The decision to reach for a snack, prepare a meal at a specific time, or engage in a particular food-related ritual involves coordinated activation of multiple neural circuits. Through repetition, these circuits become increasingly integrated and efficient.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter central to reward anticipation and motivation. Contrary to older views that dopamine represents pleasure, modern neuroscience understands dopamine as fundamentally involved in reward prediction and motivation to act. When a behaviour consistently produces a rewarding outcome, dopamine systems learn to anticipate that reward.

In habit contexts, dopamine's role shifts over time. Initially, dopamine fires in response to the actual reward (taste of food, sensory satisfaction). With repetition, dopamine increasingly fires in anticipation of the reward—in response to the cue that predicts the reward. This shift is central to automatic behaviour: the cue itself becomes motivating, driving behaviour without conscious deliberation.

The basal ganglia, a collection of neural structures deep in the brain, are crucial for translating learned patterns into automatic actions. While the prefrontal cortex—involved in conscious decision-making—is highly active when we learn new behaviours, routine execution of learned habits increasingly relies on basal ganglia activity.

This shift from cortical to subcortical control is what enables automaticity. A behaviour that initially required conscious attention and deliberation gradually moves to automatic execution as basal ganglia systems take over. In eating contexts, this explains how a routine morning meal pattern eventually requires minimal conscious thought—the basal ganglia automatically initiate the sequence.

Neural systems do not simply encode "perform behaviour X." Instead, they encode "in context Y, perform behaviour X to receive reward Z." The context—the cue—becomes tightly associated with the behaviour and reward through a process called cue-dependent learning. Specific brain regions, particularly the hippocampus and surrounding temporal structures, encode contextual information.

When the same context recurs, previously learned neural patterns reactivate, reinstating the motivation and automaticity associated with that context. This is why returning to a familiar location, experiencing a particular time of day, or encountering a specific visual cue can automatically trigger associated eating behaviours—the neural patterns encoding those associations have been strengthened through repetition.

Habits are possible because of synaptic plasticity—the ability of neural connections to strengthen or weaken over time. Repeated activation of a neural pathway causes structural and chemical changes in synapses, including increased neurotransmitter receptors and altered neurotransmitter release. These changes make future activation of the pathway more likely and efficient.

The timescale of habit formation varies depending on the frequency and consistency of repetition, the consistency of context, the magnitude of reward, and individual neural variation. Generally, eating habits can become increasingly automatic over weeks to months of consistent repetition in stable contexts.

An important aspect of neural habit encoding is context-dependence. Habits are fundamentally tied to the contexts in which they were learned. Different contexts can support different automatic behaviours, even if they're superficially similar. This is why changing environment can sometimes disrupt established patterns—the contextual cues that typically trigger automatic behaviour are absent.

This context-dependence is neither negative nor positive; it's simply how neural systems function. Understanding it helps explain why habits are both stable (they persist in consistent contexts) and modifiable (they can differ across contexts).

While the basic principles of habit formation through neural strengthening apply universally, the speed and ease of habit formation varies substantially between individuals. This variation reflects differences in dopamine signalling, neural plasticity rates, sensitivity to contextual cues, and other individual neural characteristics.

Some individuals form strong habitual associations quickly, while others require more extensive repetition to develop similar automaticity. Neither variation represents a deficiency; they reflect natural neural diversity.

Educational Note: This article presents neuroscientific information for educational purposes. It explains general principles of how the brain supports habit formation. This is not medical information, and individual neural function varies. For specific health or neurological concerns, consult qualified professionals.